The story heard word of mouth: The Sunshine Skyway bridge was originally opened in 1954 to connect Pinellas with Manatee county. The tallest bridge in the area, it already gained a reputation for attracting suicides. A few years after it was opened, a woman jumped into the murky depths of the bay below. Some believe that the span was cursed as several Native American (now an extinct tribe) middens (shell mounds) were, reputedly, destroyed in creating the span. Parts of the roadway leading to the bridge were built on top of the mounds' former resting places.

After that time, rumors began to circulate of a vanishing hitchhiker. Stories circulated of people who saw a beautiful blonde woman hitchhiking near the mid-span. When they stopped to pick her up, nothing seemed out of the ordinary -- she had a physical tangible presence in the car -- but as the vehicle approached the summit of the bridge, she would begin to cry. When the driver turned to ask what was wrong they'd find themselves alone in the vehicle. One account, possibly the original story, comes from The Tampa Bay Triangle (by Captain Bill Miller). This book cites a specific story of a couple who, in the 1960s, had just such an encounter.

(Brandy notes: Interviews with toll takers on the bridge were aired on the radio; toll collectors claimed that many people had the same experience).

Things get interesting because the original Sunshine Skyway bridge was hit by a freighter May 10, 1980. The central span collapsed causing the death of 36 people traveling across it at the time. The most tragic aspect is that a Greyhound bus with college students going home for the summer was one of the vehicles that fell into the water below. All on the bus were killed. Of those trapped in their vehicles on the bridge when it collapsed, only 1 person survived when their car hit the boat lodged underneath, then fell into the bay. At this time, the old span was destroyed and the current span built (with the famous yellow "sails" that some say the aliens use to "call home"). Remnants of the old bridge were left to serve as two fishing piers (one stretching from the northbound span, the other from the southbound). The new bridge and those remnants have additional stories:

The hitchhiker isn't done yet. She has, apparently, moved to the new bridge. Stories have changed her hair color to that of a brunette. It's hard to determine if this is an urban legend or not, as the new span, being taller than the old one, has had a plethora of suicides. The bridge has added phones along the top of the span for potential suicides to call for help, or for passing motorists to phone in activity. (Brandy: As of 6 months ago, I have a friend of a classmate who jumped. It is an active site).

The fishing piers are said to be haunted. The Tampa Bay Triangle sites two fishers who were on the pier early in the morning of May 10, 1990. At the time of the original span's destruction, the two men felt an eerie presence. One man saw the a spectral bus, all people sitting bolt forward with looks of terror on their faces. The bus passed them by; the astounded witness saw one person in the back of the bus turn around and wave at him, smiling.

The fishing pier also links to another legend: the Flirty Fisherman. (We'll be checking that story soon).

There is an additional rumor relating to the bus. Apparently, once fished out of the bay, Greyhound used the bus parts that they could salvage in other buses. Any bus that had one of these parts in it allegedly burst into flames. This sounds remarkably like the story of the remains of Flight 401, another transportation tragedy in Florida. A plane crash landed in the Everglades, killing all on it. The salvaged parts were used in other planes and apparently brought along the ghost of one of the crew members, who only appeared during times of crisis.

Other accounts of stories: http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/236359/the_haunted_skyway_bridge_in_florida.html?cat=8

Sunshine Skyway: Ghostly Jumpers, Vanishing Hitchhikers

August 10, 2007: After the Florida Ghost Conference in Clewiston, Florida:

EMF was unusually high on the Southbound span up through the center of the span. The meter was registering about a 6.0 EMF through most of the trip. It is hard to determine if the EMF was created from the car or from something on the bridge.

All images were taken from a moving car (it is very hard to pull over on the bridge). Nothing unusual appeared. Members have crossed the bridge individually and none report any unusual phenomena.

Other sources:

Reeser, Tim. Ghost Stories of St. Petersburg, FL:

The Story submitted by email:

I am a witness to the hitchhiker. I have seen her several times - every time she is jogging along the causeway. Except for one time, when I was at the top of the bridge in 1998. I was looking down into the water when the hitchhiker jogged right past me, said "don't do it" and then went on her way down the slope, disappearing from view. She is a fairly tall, slender girl with blonde hair down to her shoulders. She was wearing a hooded shirt that night. I didn't know she was a spirit until that night. I saw her several times jogging along the causeway after that, but it's been a few years since I've seen her. I really don't travel that way, not since 2002.

by email:

Regards,

Judy

My spirit adventure could not really be classified as a true adventure with “spirits” as I was traveling in a van with 9 other people, on a terrible cold and windy night, shortly after the accident at the bridge. It was creepy to begin with, and as we came to a halt at the top of the bridge span (due to a traffic problem) I could look over and see the mess of the bridge span that had collapsed. I felt a hovering presence there…..I have had that before under similar disaster circumstances – and could not shake the sense of “presence” and doom. It was horrible, and wrecked what might have been a fun evening! -- GR.

Eckerd College Search and Rescue

History The Eckerd College Search and Rescue Team (EC-SAR) is a unique co-curricular program that cannot be experienced at any other educational institution in the US. The team was founded in 1971 in an effort to provide safety services for the college's watersports activities. In 1977, EC-SAR extended its rescue services to the Tampa Bay boating community. EC-SAR received its first test of international proportions when the team was one of the first rescue units to respond to the Skyway Bridge disaster in May of 1980. The program has since grown to become one of the most respected search and rescue organizations on the west coast of Florida.

Article of the accident:

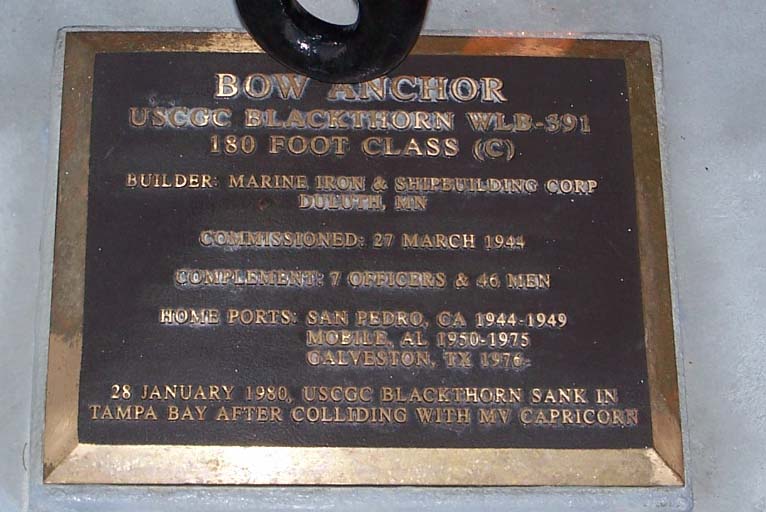

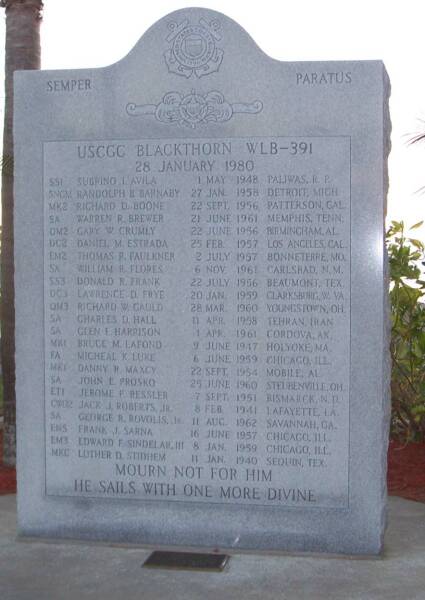

At 7:25 a.m. on May 9, 1980, with the Greyhound approaching Pinellas Point a few miles from the north end of the Sunshine Skyway bridge, Capt. John Lerro tensed at the helm of the freighter Summit Venture, a ship as long as two football fields. Lerro, 37, an experienced harbor pilot from Tampa, shouldered the responsibility of guiding the Summit Venture from the Gulf of Mexico 58.4 miles up Tampa Bay to the Port of Tampa. It is one of the longest shipping channels in the world, and one of the most treacherous, given the shallow waters of the bay and the ambush style of Florida weather. With the ship's belly empty of cargo and her tanks nearly empty of ballast, she rode high in the water. She ran through intermittent fog and rain along the first 19 miles of her journey. Then southwest winds exploded to tropical-storm force. Rain sheeted at rates exceeding 7 inches an hour. Visibility plunged to near zero, and shipboard radar failed. It couldn't have happened at a worse point. Lerro faced the most critical course change of the run, a 13-degree turn that would take him between the two main piers of the Skyway bridge. It was at almost this exact spot that the Coast Guard cutter Blackthorn had been rammed four months earlier by the tanker Capricorn. The Blackthorn sank. Twenty-three men died. Lerro approached the critical bend on a ship weighing nearly 20,000 tons battered by winds of nearly 60 mph.

20 years after Florida Sunshine Skyway disaster

Bradenton Herald

Skyway tragedy: Editorial page editor David Klement's 20th anniversary story

DAVID KLEMENT

Herald Editorial Page Editor

The early morning of May 9, 1980, felt like a day without a dawn. Going outside to fetch something from the car at about 7:30 a.m., I was struck by the pitch darkness of the sky, as if the night hadn't ended at its normal time. That inky blackness, I would soon learn, would be the cause of - and fitting backdrop for - the horror that was to come.

It was so dark, my wife and I discussed the wisdom of letting the kids walk to the bus stop, all of 200 feet from our front door. As we scurried to get their lunches packed and backpacks organized, we volleyed over who was in the better position to drive them to school. She had an early appointment outside the office; I had my usual Friday morning crunch of preparing Opinion Page content for the weekend editions of The Herald.

As I scanned the black sky for some sign of the oncoming storm's direction, little did I know that, within a few minutes, my routine would be turned upside down and I would be facing one of the most incredible news events of my life.

My immediate thoughts were on tornadoes. Twenty-two years of living in the flat expanses of Texas had taught me that this was the kind of sky from which tornado funnels dipped. I didn't mention that thought later when I got to the newsroom, though. We'd been through enough Florida thunderstorms to know better than to get excited every time the sky turned black. Why, this could all blow over in a few minutes. The rain would be good for the lawn, the school bus would be along shortly and, once safely on it, the kids were in good hands.

That was the kind of ambivalence with which we began our day, not knowing that about 15 miles away a 609-foot freighter named Summit Venture, buffeted by 60-mph winds and steering through this very storm's blinding rain and darkness in near-zero visibility, was headed for disaster at the mouth of Tampa Bay.

With empty cargo holds and empty bilge tanks, the giant freighter, longer than two football fields, was a 19,735-ton floating cigar box, pushed by the storm's howling gales some 800 feet out of the shipping channel designed to take it safely beneath the Sunshine Skyway Bridge. At about the moment our children boarded the school bus and we drove to work that Friday morning, the Summit Venture smashed into the second support column south of the bridge's highest span, crumbling the column and taking out 1,297 feet of roadway and superstructure at the bridge's pinnacle, 150 feet in the air.

In the next few sickening moments, 35 people on the road above - ordinary people like us on their way to work, appointments, family reunions - met death in one of the most horrible ways imaginable: driving off the shattered end of the bridge into thin air and falling, falling, falling into a spaghetti-like tangle of steel girders, broken concrete and roiling water below.

Newsroom mobilizes

As day-shift employees arrived at the Herald on 13th Street West in downtown Bradenton around 8 a.m., a handful of editors and reporters from the city desk, news desk and sports desk had already been at work for several hours, preparing copy for the first edition.

As an afternoon newspaper then, the Herald had to be in news racks and stores by 11:30 a.m. and on the way to customers' homes by 1 p.m. The newsroom's first word of the Skyway disaster came from the pressroom. A printer had heard a bulletin on the radio. The first reaction of many in the newsroom was disbelief. Surely this was someone's idea of a sick joke. But it merited checking out.

A reporter called the Skyway tollgate office on the north end. A toll collector confirmed that something terrible had happened on the bridge but didn't know what. The staff mobilization quickly started. Someone began calling off-duty reporters to come in immediately, and every warm body was drafted for an assignment. Our Tallahassee reporter, Joe Parham - back from covering the close of the Legislature only a few hours before - and a photographer headed for the bridge. Chief photographer Carson Baldwin was authorized to charter a plane to get aerial shots of the scene. Outdoors writer Jerry Hill began calling fishing buddies looking for boats to borrow. Then-Publisher Bill LaMee volunteered his own boat and a marine team was dispatched. Reporters were dispatched as they arrived: one more to the Skyway; another to the bus station in Sarasota where a Greyhound was overdue; another to Mullet Key in Fort De Soto Park in Pinellas County, where victims' bodies would be taken for transport to a morgue in Tampa.

Others were on the telephone to the Coast Guard, to the Journal of Commerce in New York for background on the ship, to the engineering firm that designed the bridge, to witnesses or relatives of potential victims. Twenty years later, I cannot remember exactly what I did in those crucial few hours before we had to have a newspaper on the street. I know there was no hysteria and very little emotion as we worked to cover the story of a lifetime. Professional instincts - and adrenaline - kicked in to overcome the shock of the event; the atmosphere in the newsroom was businesslike. Later, though, pent-up emotions would give way to shock. One former copy editor admits today that, after finishing her shift, she went home and wept, thinking about the victims: 'It was one of the few stories I ever cried over.' Throughout the Tampa Bay area, others were rocked by similar emotions. So many could identify with this bridge, a truly breathtaking landmark in Manatee and Pinellas counties.

Yet those of us with fears of great heights always had a vaguely unsettling feeling about the Skyway. Its spider-web-like steel superstructure perched on skinny concrete piers seemed a rather fragile connection to Earth. From a distance it looked more like a child's Erector Set project than a feat of modern engineering that connected two peninsulas across 15 miles of Tampa Bay.

Up close, its narrow lanes, built for the small cars of the post-war '40s and early '50s, afforded no room for error. You gripped the steering wheel with both hands and shut out all distractions when crossing the Skyway, trying to block mental images of losing control and going off the edge or, God forbid, a freighter crashing into the bridge as you crossed. On this day, that vision became reality for several dozen people, 35 of whom died and a handful of whom lived to tell about it. Many people were imagining their horror as they waited for news of the crash.

Rescue sparks hope

The details that are now indelibly imprinted in the memories of all who were here at the time were slow to trickle in that morning. Vehicles had driven off the shattered end of the bridge at its highest span during what some called a mini-hurricane; no one knew how many.

A loaded Greyhound bus was believed to have been among them, and possibly a bus full of migrant workers. Then word came that the driver of one of those cars was alive. Somehow Wesley MacIntire escaped from his little Ford pickup truck after it plunged off the bridge, ricocheted off the Summit Venture and began to sink in the bay.

His rescue sparked hope that perhaps others would be saved, that this would not be the human disaster we feared. Around mid-morning, with the clock ticking toward a late deadline of 11:30 a.m., the Herald got a big break. Advertising sales representative Don Albritton arrived for work, pale and shaken. A resident of St. Petersburg, he had been on the bridge when the ship struck it. Albritton's dramatic, eyewitness account of the nightmarish scene put into words the visions readers had of what it must have been like on the bridge that morning.

'The superstructure started to come down,' Albritton said. 'I slammed on my brakes, threw my car into reverse and started to blow my horn and yell at other passing cars. ... It was raining heavily, and the bridge began to shake just like an earthquake. Large girders began to crash down. ... I think I was the second to the last car to go over the bridge before it happened.' And, he confirmed, a bus 'went roaring by' despite his efforts to warn the driver to stop.

But others were luckier. Richard Hornbuckle and three co-workers from a St. Petersburg auto dealership, en route to Avon Park to pick up vehicles, were near the top of the span with the wind 'blowing like a hurricane' when traffic ahead came to a stop. He jammed on the brakes to avoid a rear-end crash just as the roadway ahead - including the cars in front of him and a bus that came flying by on his left - disappeared. His panic stop put his car into a skid on the bridge's slick metal grating.

It came to a halt a heart-stopping two feet from the edge. The sight of Hornbuckle's yellow Buick on the lip of a precariously dangling section of bridge became an iconic image of the Skyway story. In those days before cell phones, editors communicated with reporters and photographers in the field via two-way radios in their cars.

But all of the photographers and reporters had been forced to leave their cars near the bottom of the intact but now-closed northbound Skyway span, so they had to walk up the bridge to view the scene and interview public safety officials directing rescue and recovery efforts. With the clock ticking away, we had to get film back and begin processing it to have pictures in time for the first edition.

A copy editor was delegated to drive a company van to retrieve the film. But first he stopped at his home in Palmetto, loaded up a bike belonging to one of his sons, and drove to the foot of the Skyway. He rode the bike up the steep grade of the bridge, met our photographer at the top, got his film and headed back. For an out-of-shape, 30-something father of three, the ride down was as terrifying as the ride up was hard, but he returned with the film in time to make deadline.

Life-saving delay

Amid the heartbreaking stories of loss in that first day's report were heartwarming stories of good fortune. One was about Manatee County schoolteacher Terry Butterfield, who normally would have been crossing the bridge just about the time the ship struck it but was running late because he stopped to iron a fresh pair of trousers after noticing a stain on the pair he was wearing.

Frustrated because he was late for work and stuck behind slow-moving traffic on the rain-swept bridge, Butterfield was about to pull to the left to pass when he saw a car pulled off in the emergency lane with the driver waving frantically.

Thinking the driver had run out of gas, Butterfield recalled a sermon he had heard in church Sunday on the theme: We are our brother's keeper. He pulled over in front of the stalled car and got out to see how he could help the driver.

It was Don Albritton, and his greeting was chilling: 'The bridge is out.' Friday's first edition, which came off the presses around 12:30 p.m., contained many of those details in its three pages of Skyway-related content. We were the first paper on the street in Manatee County with coverage of the tragedy, and pressmen recall we upped the press run by as many as 1,000 additional copies to meet demand. The edition, published barely five hours after the tragedy occurred, contained a lead story with a surprisingly accurate account of the fatalities, 32 - just three fewer than the ultimate death toll would prove to be. Dramatic aerial shots showed a shattered bridge, rescue efforts on the water, and a haunting image of the Summit Venture at anchor to the west of the broken bridge, shards of girders and highway asphalt dangling from its enormous bow like broken pieces of a child's toy.

Stories included an interview with Albritton. Front-page words told of the search for bodies. Inside was a review of the bridge's history and its accident record, which included four mishaps in a 19-day span three months earlier. One of the more vivid memories in the hours that followed was the recovery of the Greyhound bus, which carried the driver and 22 passengers to their deaths. At times as the tide receded, its outline could be seen below the surface of the water, trapped in the tangle of girders and concrete beneath one of the shattered pilings.

From the top of the north span, 150 feet in the air, it looked like a smashed Matchbox car, said one witness, its top flattened to window level by fallen girders as it plummeted into the bay.

Bradenton Mayor Wayne Poston, who was then The Herald's editor, walked up to the north bridge Friday afternoon after the paper was out to see the scene for himself. He called it 'a chilling thing. It was an incredible vision. I just couldn't imagine this happening.' Watching a crane lift the crumpled bus from the water and dump it on a nearby barge, he said, 'was horrible. I imagined the people on the bus, and how the fall must have seemed like an hour to them.' Saturday was no day off for most of us. There was still a great deal of reporting to do as more bodies were recovered, victims were identified, and analysis of what went wrong began to emerge. Many of us helped produce a 12-page section that went into the Sunday edition, a compilation of the highlights of our previous coverage.

Earlier warnings ignored

Sunday also brought the first attempts at assessing blame, and here the real shock of the tragedy began to take on new dimensions. The Skyway, it turned out, had been an accident waiting to happen - had indeed happened many times before in less dramatic ways. But the warnings had been ignored.

In our Sunday editorial headlined 'A tragedy that shouldn't have happened,' we recounted the startling series of accidents in the two previous years, including one just the previous Feb. 16 involving the same pilot in what in retrospect seemed an eerie dress rehearsal for the Summit Venture disaster.

Like an accursed Captain Ahab, John E. Lerro, piloting the 720-foot Janna Dan into Tampa Bay on Feb. 16, tried to maneuver around the wreckage of the Coast Guard cutter Blackthorn, misjudged his detour and put the huge freighter into the path of the Skyway. The bow stopped short of the bridge, but the stern - its holds empty and riding high in the water just as the Summit Venture's would - was pushed by the current and strong winds toward a bridge piling.

It sheared off a protective wooden fender like a toothpick before crashing into the piling. Fortunately for the motorists who foolishly stopped to gawk, Lerro's error left only a 10-foot-long, 2-inch-deep gash in the piling, and no structural damage. Coming so soon after the Jan. 28 sinking of the Blackthorn, which cost 25 lives in a collision with a tanker, this accident should have sounded alarm bells about the Skyway, but it did not.

The real precursor to the Summit Venture had occurred two years earlier on May 2, 1978, when the 851-foot Phosphate Conveyor ore carrier lost power about a half-mile from the Skyway. As the crew frantically worked to stop the ship, the engines restarted and the anchor held. The ship stopped just 40 feet from the bridge.

Florida Department of Transportation engineers said at the time that a direct hit on one of the main supporting piers would have toppled the pier and the bridge with it. But nothing was done to strengthen the wooden fender system that was supposed to repel stray vessels.

No state-of-the-art navigation system was installed to guide ships more precisely along Tampa Bay's winding 40-mile shipping channel and through the '800-foot hole' between the bridge's concrete columns. No rules against traversing the Skyway during heavy weather were implemented. And no vehicular traffic barriers were installed on the roadway to stop drivers when a ship was passing under the bridge, as some suggested.

In retrospect, the tragedy that occurred May 9, 1980, seemed entirely preventable, adding unfathomably to the sorrow for the 35 victims' grieving relatives and to the shock throughout the Tampa Bay community. Those of us who drove the bridge regularly watched the tragedy unfold in stunned fascination, as if we had somehow expected it to happen someday. Now we no longer had to wonder what it would be like to go off the edge. We had seen it.

__________________

09-11 .. 343 'All Gave Some..Some Gave ALL' God Bless..R.I.P.

------------------------------

IACOJ Minister of Southern Comfort

'Purple Hydrant' Recipient (3 Times)

BMI Investigator

------------------------------

The comments, opinions, and positions expressed here are mine. They are expressed respectfully, in the spirit of safety and progress. They do not reflect the opinions or positions of my employer or my department.

8-9-08: Returning from an investigation in Sarasota. This image was taken at 10 p.m. through an open car window. The EMF meter was on and spiked on "Did you commit suicide here?" And "What was the last year you remember?" (series of years announced) Spike on "2000". Granted, the conditions for images were not perfect, and the bridge isn't a good place for EM readings, but these two questions proved interesting.

Paranormal Investigation, 11/16/08:

Paranormal Puck attempt:

User: Is there anything here?

your

User: Is this the vanishing hitchhiker?

keep legs

several User: Is this the flirty fisher?

glove history

User: Are you related to the buss?

lick france .

User: Is there a ghost at the water fountain?

door ambition test

User: Is there a ghost at the gaurd station?

among

User: Are you male?

he's Robert .

User: Are you femaile?

thank

User: Is your name Robert?

.

comfort deep

User: Did you die on the bridge/

seek cattle

User: Did you die on the bus that went the bridge?

memories vector coast

User: Is this totally random?

position

User: Do you stay in this building?

ass find finger

User: Are you a vagrant?

.

movement

User: Did you jump from the bridge?

sand told remote

User: So is there anyone here?

anything video legs

User: KIf I use the video camera, will you appear?

hole pounds empath

User: What does that mean?

rapture

User: Is there anything that you want to share with us?

bird

Interviews with people on bridge:

1: Knew story but hadn't seen anything; out every weekend

2: Knew story, no ghosts

3: Group, no.

4: New to the area, no stories.

5: Couldn't tell you about it.

Heard that the gaurd station had a ghost. Interviewed the gaurd:

No, a friend was playing a joke and alluding to him that he had a 'ghost' in the guard shack. He didn't think it was haunted.

Drove the bridge a lot; no ghosts. Only heard of the vanishing hitchhiker. Nothing on this fishing pier.

General discussion:

Bridge was unhappy feeling. All agreed it was rather creepy, not fun. It has a "abandoned feel", "void of emotion",

despite the fact that it is filled with kids and families and should have more experience to it. Bus accident is at the back of the mind --

creepy feeling. Group wondered if the ghostly activity is on the east span of the North pier. This part of the bridge is currently closed.

We would like to try the South Pier which is still open, to see if it feels different than this one.

Note: On Nov. 20, 2008, a man jumped from the Skyway to his death, as reported by the St. Petersburg Times.

May 9, 2015:

Memorial posted for the 35th anniversary of the bridge collapse:

Urban Legends of Pinellas County

2018 was a record uear for suicies on the bridge: https://www.tampabay.com/news/publicsafety/as-record-year-ends-florida-studying-suicide-prevention-barriers-for-sunshine-skyway-bridge-20190104/